Rosettes to RuinMaking & Breaking Dogs in the Show Ring Changes in the shape of the Bull Terrier head, 1930, 1950, 1980 Photos courtesy of the Albert Heim Foundation for Canine Research, Berne, Switzerland The pictures above are a physical and visible monument to what the show ring did to one terrier breed in less than 50 years time. Bulldog and terrier crosses, which once had powerful jaws well-placed to do important work (gripping and holding semi-wild bulls and pigs so they could be altered or slaughtered), were rapidly transformed at the turn of the 20th Century to the point that the jaws of today's Bull Terrier, while still massive, are now no longer set at a proper angle to do the work the dogs were once bred to do. If you look at the Fox Terrier, you will see a similar transformation over time -- once small and supple dogs transformed into large, stiff-legged creatures unable to move properly in the field and with chests too deep for the animal to go to ground after fox. This is what show ring breeders do -- they ruin working breeds. And it is not just the AKC show ring, either -- it's the UKC show ring and the JRTCA show ring as well. Give any show ring enough time, and it will ruin any breed of working dog -- it always has and it always will. Go through John Broadhurst's excellent new book, "Terriermen & Terriers" (ISBN 0-0687296-1-4) and look for Welsh Terriers, Border Terriers, Wire Fox Terriers, Smooth Fox Terriers, Cairn Terriers, Lakelands, Skye Terriers, West Highland White Terriers, Cairn Terriers. They are simply NOT there. Instead you see terriers that are not registered or are unregisterable -- Jack Russells, Fell Terriers, Fell-Border crosses, and the black Fells called Patterdales. There's even a Dachshund. The only terrierman named working a Kennel Club breed (53 terriermen are profiled) is a single fellow who recounts a Border Terrier story that is now more than 30 years old. "Working" terrier breeds? Ha! It seems they are all gone -- shot dead by the show ring. Former AKC President Kenneth Marden has acknowledged the role of the show ring in killing off working breeds: "We [the AKC] have gotten away from what dogs were originally bred for. In some cases we have paid so much attention to form that we have lost the use of the dog."I should say! In the February 13, 2002 edition of The National Review magazine there is an article entitled "The Westminster Eugenics Show" in which the author writes of the Search And Rescue dogs trotted into the Westminster Ring in New York after the September 11th terrorists brought down to the twin towers of the World Trade Center: "The problem is that Westminster does not judge breeds for those traits which rightly make a breed a breed. The Pointers aren't asked to point (even though the logo of the Westminster Kennel Club has been a pointing Pointer for over a century). The Bassets and Bloodhounds do not track. The Otter Hounds are not tested to see if they could kill, let alone identify, an otter. And so on and so on."With the exception of a handful of breeds who were bred to do nothing but either keep your hands warm or wait until some Aztec chef could cook them, not a single breed at Westminster is expected to do what it was bred to do. The beautiful German Shepherd in the competition last night no doubt looked at the visiting search-and-rescue dogs the way Alec Baldwin looks at people who actually know how to read, and said, 'I wish I could be like them.'"The cohost of the Westminster broadcast repeatedly declared 'This is not a beauty contest... because we have definitions for how a dog is supposed to look and feel.'"Someone needs to tell this blow-dried Afghan-breeder that that makes it more of a beauty contest, not less of one. Simply writing down the criteria does not make a pageant any less of a pageant." The number of working dogs ruined by the show ring grows every year. Irish Setters, once famed at finding birds, are now so brain-befogged they can no longer find the front door. Cocker Spaniels, once terrific pocket-sized birds dogs, have been reduced to poodle-coated mops incapable of working their way through a field or fence row. Fox terriers are now so large they cannot go down a fox hole. Saint Bernards, once proud pulling dogs, are now so riddled with hip dysplasia that it's hard to find one that can walk without surgery in old age. In recent years, protectors of at least two working breeds -- the Border Collie and the Jack Russell Terrier -- have gone to war with the AKC in an effort to protect the working qualities of their dogs. Unfortunately, those seeking to protect the gene pool of working dogs -- and the tradition of breeding worker to worker -- lost and both breeds are now found in the AKC show ring. While there are still working Border Collies and working Jack Russell Terriers, the number of honest working dogs of either breed in the AKC show ring is small and is falling rapidly. In time it is likely that these two breeds will in fact split off from their working roots as has happened with gun dogs where there are "working" labs and "show labs" and "working" pointers and "show" pointers. Lesson One in the world of dogs is that if you put anything above breeding for utility, you will start to lose working abilities. Work is a tough task master and it shows no favoritism. Fox and pheasant do not judge "up the leash" nor are they taken in by fads. Quarry is not much interested in nose or eye color, the set of the ear, or the "expression" on a dog's face as it creeps up a hedgerow. In working dogs, utility is beauty, and "beauty is as beauty does." E.L. Hagedoorn, a Dutch consulting geneticist to dog breed societies around the world, believed the show ring would ruin working dog breeds, and time has proven him right. As he noted in his 1939 book: "In the production of economically useful animals, the show ring is more of a menace than an aid to breeding. Once fancy points are introduced into the standard of perfection, the breeders will give more attention to those easily judged qualities than to the more important qualities that do not happen to be of such a nature that we can evaluate them at shows. Showing has nothing to do with utility at all, it is simply a competitive game."A noted breeder of alpacas said much the same thing, noting that when farm stock is judged on the basis of wool or meat it is a different standard than that used at shows: "Breeding animals for the shows is a very peculiar business, because of the fact that it is wholly competitive. Whereas the breeder of utility sheep or utility pigs produces something that has a certain market value, which is not changed very much even if ten of his neighbors start in with him to raise the same sort of sheep or hogs, breeding animals for the shows can only pay the man who succeeds in producing such stock as is pronounced by the judges of the moment to be the most beautiful and the most fashionable." The "judge of the moment" in a show ring may know very little about real terrier work. In the AKC, for example, most judges are experts in a half dozen breeds. In the terrier ring, it's almost a guarantee none has ever owned a deben collar or cut a shoulder into a trench in order to get down another two feet. As a rule these authorities are experts by dint of having spent far too many nights in bad hotels attending show trials. In 20 years of owning dogs, they have logged a thousand miles bouncing around show rings in plaid skirts and blue blazers. They may have driven to the moon and back to pick up rosettes, but few have driven 10 miles out into the country to even see a fox den, much less put a dog down one or dig to it. A few will claim expertise because they have bought an airplane ticket and attended a mounted hunt or two in the U.K.. They have seen "the real thing" they will tell you, and know what is required of a working dog thanks to their two-week vacation in Scotland! Just don't ask them how to extract quarry from the stop-end of a pipe or how to treat a bite wound. Theory always ends where reality begins, and it always seems to have been this way. The very first Kennel Club shows occurred in 1873 in the U.K., and 1874 in the U.S.. By 1893 Rawdon Lee Briggs was writing in his book, "Modern Dogs," that: "I have known a man act as a judge of fox terriers who had never bred one in his life, had never seen a fox in front of hounds, had never seen a terrier go to ground ... had not even seen a terrier chase a rabbit."By the AKC's own estimates, a majority of newcomers to the sport, obsessed with championship ribbons, stick with it an average of five years. When they give up or move on to a new hobby, they leave behind a trail of dogs that were not systematically bred to do a job -- they were bred to produce ribbons and often by people who never completely finished reading a book on their own breed. Most of these back-yard-and-hobby-show-breeders do not do any genetic testing on their dogs, and when asked are quick to say their bumbling acquiescence to the destruction of a working breed is OK because "No one's hunting birds to feed their families any more," "We don't need strong jaws on a bull terrier, we have barbed wire now" "No one hunts fox anymore -- it's illegal in the UK you know." I would suggest to these people that they get deeply involved in breeds that are not working breeds -- Shit-zoos, Peeking-ease, or Pappy-yawns, perhaps. Miniature Schnauzers or Miniature Pinschers are nice dogs -- give them a try. Or better yet, get a dog from the local shelter and train it in to a high degree of perfection in agility, flyball or even circus tricks. But please stay away from breeds that are working dogs! As for those actually interested in terriers as working dogs (and if not, please read the paragraph above), we would do well to remember that we did not create these wonderful little dogs, and we do not 'own' a breed anymore than we 'own' anything in this world. Like most worthy things, we inherit our dogs from our forbears, serve as custodians for their gene pool in our lifetime, and have a responsibility to pass on this gene pool in a reasonably good condition for the future. In the modern world, passing on the gene pool means breeding dogs that are the correct size as determined after you have done some real earth work. It also means doing genetic testing (CERF, OFA, BAER) before breeding any litter. For those looking to buy a terrier -- especially a Jack Russell or Border Terrier which are two breeds which still have some pretensions to being working dogs -- I would suggest embracing a working standard, not only for the dog but for the BREEDER as well. If the breeder doesn't own a deben collar, a $50 shovel, and a digging bar, I would suggest giving that kennel a pass. Ask to see pictures of the sire or dam in the field. No pictures, no cash. A serious breeder takes the work of their dogs seriously, and a serious breeder will work their dogs at least a few times just to make sure they have the drive, the size and the temperament to actually do the job. The standard for a working terrier is NOT in the ring, but in the field and it is only in the field that a dog can be judged worthy of being bred. I close with the very succinct and dead-on standard for working terriers published by The Fell and Moorland Working Terrier Club in their "Year Book and Club History: 1998-99". No better parody of the Kennel Club "standard" exists, nor does it leave out a single thing required of a working terrier. A Working Terrier Standard A working terrier should be terrier-like in appearance and should have an acute and powerful motivation to work.HEAD: should be strong, and encased in the skull should be a brain capable of showing intelligence and a fair amount of obedience and respect with some affection.NECK: should be strong and muscular, joining the head to the body.CHEST: should be big enough to hold the heart of a lion, but small enough to enable its owner to follow the quarry into extremely tight corners.LEGS: should be long, or short, according to the work envisaged by the terrain of the area where he is to be employed. The legs should be powerful enough to carry the owner through a hard day.FEET: four, one at the end of each leg, with extremely tough pads.COAT: whether rough or smooth, white or colored, should be dense and tight, to keep its wearer warm and facilitate cleaning without holding too much earth and water.BACK: strong and supple.TAIL: for preference, a working terrier should have a tail.EYES: of great assistance above ground.EARS: yes, two.NOSE: should be able to detect and evaluate any slight scent.TEETH: should be as large and as strong as possible, firmly secured in a muscular jaw, capable of biting powerfully and holding a firm grip.In temperament, the animal should be fairly docile and tractable, with a tremendous staying power and great love of his task. He should enjoy going to ground and should not appear at 10 minute intervals to see if his owner is still waiting for him. He should disregard wounds and see his job through at all times. He should be of sensible disposition and not easily ruffled or upset. Show ring bulldog skull This is a long way from a working dog!

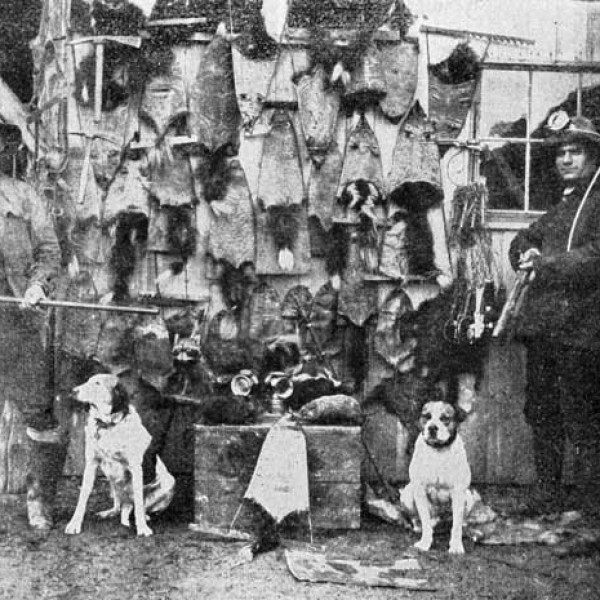

Night hunting is a favorite form of hunting sport the continent over. Prime factor of the joyous, though strenuous night quest is the 'coon, the court jester and wit of the nocturnal tribe of small fur bearers. Fruits of the night hunt Owing to the scarcity of other game and general distribution of raccoon the country over, 'coon hunting is gaining in popular favor, winning over many of the wealthy, city-dwelling red-bloods who formerly were content with more or less pleasant and successful sallies to the fields in the day-time. Consequently there is an increased demand for properly bred and trained dogs to afford the maximum of success and pleasure in this pursuit. With the ownership of dogs go the care, maintenance and proper methods of handling these willing helpers. Surprising is the meagerness of the information available to the average hunter, though night hunting is an institution as old as the settlement of Jamestown. The craft of developing dogs and using them to the best advantage in this connection, has been by precept and example handed down from generation to generation. Much has been lost in this way and not so much accomplished as might have been attained by aid of the printed and pictured methods of today. Most certainly more attention will hereafter be paid to night hunting, and more painstaking records made and kept for the up-growing practical sportsmen, in which direction the present volume is a long and definite step. The Court Jester of the Nocturnal Tribe.Our task is to offer guidance and advice as to the dogs. Yet to do this clearly, the reader must know something of the nature and habits of the animals to be hunted and the effort involved. A southern gentleman of experience and training has the following to say about 'coon hunting: The 'coon is a wily little animal, and his habits are very interesting to note. He is a veritable trickster, compared with which the proverbial cunning fox must take a back seat. One of the 'coon's most common tricks employed to fool the hound is known among hunters as "tapping the tree," and which he accomplishes in this way: When he hears the hound's first note baying on trail, he climbs up a large tree, runs to the furthest extremity of one of the largest branches and doubling himself up into a ball, leaps as far as possible out from the tree. This he repeats several times on different trees, then makes a long run, only to go thru the same performances in another place. Onward comes the hound, till he reaches the first tree the 'coon went up, and if it is a young and inexperienced hound, he will give the "tree bark" until the hunters reach the tree, fell it, and find the game not there. All this time Mr. 'Coon is quietly fishing and laughing in his sleeve, perhaps a mile away. But not so with the wise old coon hound. The old, experienced cooner, with seemingly human intelligence, no sooner reaches the tree Mr. 'Coon has "tapped" than he begins circling around the tree, never opening his mouth — circling wider and wider until he strikes the trail again. This he repeats every time the 'coon takes a tree, until finally, when he has to take a tree to keep from being caught on the ground, the hound circles as before and, finding no trail leading away, he goes back to the tree, and with a triumphant cry proclaims the fact that he is victorious. He is not the least bit doubtful. He knows the coon went up the tree and he know he has never come down, so he reasons (?) that the coon is there, and with every breath he calls his master to come and bag his game. When the tree is felled, the fun begins. The 'coon is game to death. He dies fighting — and such a magnificent fight it is! The uninformed might suppose there would not be much of a fight between a 50-pound 'coon hound and a 20-pound 'coon. Well, there is not, if the 'coon hound is experienced and knows his business. Of course, the 'coon will put up a masterly fight, and some time is required to put him out of business; but the old 'coon dog will finally kill any 'coon. But if the fight is between a young or inexperienced dog and a full grown 'coon the chances are that you will suffer the mortification of seeing your dog tuck his tail between his legs and make for home at a very rapid and unbecoming rate of speed. To prove this, get a good 'coon hound and let him tree a 'coon; have along your Bull-dogs, Bull Terriers, Pointers, Setters, Collies, or any other breed you believe can kill a 'coon; tie your 'coon hound, cut the tree, and let your fighters on to the 'coon, one at a time or in a bunch, and see them clay him. You will see the old 'coon slap the faces off your dogs, and the shortest route home will be all too long for them. Killing a 'coon appears to be an art with a dog, and, of course, much more easily acquired by a natural born 'coon hound than by a dog of any other breed. A year-old hound of good breeding and from good 'coon hound parents, can kill a 'coon with less ado about it than half a dozen of any other breed. It is in swimming that the 'coon is most difficult to handle. I have known several hounds to be drowned by 'coons in deep water. The dog goes for the 'coon, and the 'coon gets on top of the dog's head. Down they both go, and, of course, the dog and 'coon both let go their hold on each other. Again, the dog grabs the 'coon, and under the water they both go. This is repeated, until the dog becomes exhausted, his lungs fill with water, and old Mr. 'Coon seems to understand the situation exactly and seats himself firmly on top of the dog's head, holding him under the water, till outside assistance is all that will save him from a watery grave. As there is but little chance — practically none — to kill a 'coon while he is swimming, the wise old 'cooner, on to his job, will seize the 'coon, strike a bee line to the bank, and kill him on terra firma. I once saw a big old boar 'coon completely outdo and nearly drown a half dozen young hounds in Hatchie River, when an old crippled hound, with not a tooth in his head, arrived on the scene, plunged into the river and brought Mr. 'Coon to the bank, where the young hounds soon killed him.